Explore our pathway

Universities are reacting with strong determination and creativity to the new challenges they face. Budget deficits have mushroomed following sudden declines in education funding and limits on tuition increases. Competitiveness in the global job market is making new programs, new training and new models of instruction an essential Ingredient in order for students to obtain gainful employment after graduation. Amidst a vastly fluctuating student population, universities are hamessing new technologies, such as e-learning, as a way to reach even more students. These place the core academic missions of teaching, research and outreach at risk To help bring the back the focus to schools’ core missions

International student mobility

One of the aspects of tertiary education which Education at a G/ance tracks each year is international student flows. reveal a sharp reversal of trends in the year that COVID-19 This is an area where future editions of this publication may To ensure the continuity of education despite the lockdown, higher education institutions have sought to use technology and offer online classes and learning experiences as a substitute for in-class time. However, many universities struggled and lacked the experience and time they needed to conceive new ways to deliver instruction and assignments

When and how to reopen school

A survey recently conducted by the OECD and Harvard University on the education conditions faced in countries and on the approaches adopted to sustain educational opportunity during the pandemic has found that the learning that has taken place during the period when schools were closed was at best only a small proportion of what students would have learned in school (Schleicher and Reimers, 2020. The period of learning at home has made visible the many benefits that students gain from being able to learn in close contact with their teachers and peers, and with full access with the wide variety of educational, social and health-related services which schools offer. This public awareness of the importance of schools and of teachers could be strategically deployed to increase engagement and support from parents and communities for schools and for teachers. This will be particularly important in the current context as the health and econoric costs of the pandemic risk reducing the funds available to education. There are unquestionable benefits to reopening educational institutions in terms of supporting the development of knowledge and skills among students and increasing their economic contribution over the longer term. In fact, the learning loss which has already taken place, if left remedied, is likely to exact an economic toll on societies in the form of reduced productivity and growth. Reopening schools will also bring economic benefits to families by enabling them to return to work, once public health authorities deem that this is feasible.

The impact of COVID-19 on education at a glance

This brochure focuses on a selection of indicators from Education at a Glance, selected for their particular relevance in the current context. Their analysis enables the understanding of countries’ response and potential impact from the COVID-19 containment measures. The following topics are discussed As the world becomes increasingly interconnected, so do the risks we face. The COVID-19 pandemic has not stopped at national borders. It has affected people regardless ofnationality, level of education, income or gender.

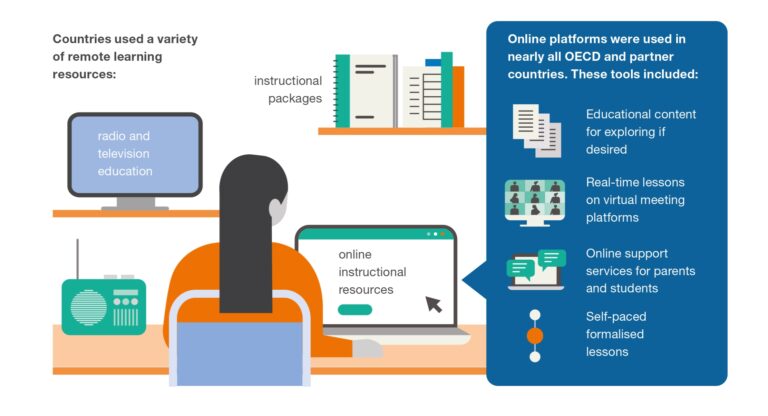

But the same has not been true for its consequences, which have hit the most vulnerable hardest. The lockdowns in response to COVID-19 have interrupted conventional schooling with nationwide school closures in most OECD and partner countries, the majority lasting at least 10 weeks. While the educational community have made concerted efforts to maintain learning continuity during this period, children and students have had to rely more on their own resources to continue learning remotely through the Internet, television or radio. Teachers also had to adapt tone pedagogical concepts and modes of delivery of teaching, for which they may not have been trained. In particular, learners in the most marginalised groups, who don’t have access to digital learning resources or lack the resilience and engagement to learn on their own are at risk of falling behind.

Measures to continue student's learning during school closure

A survey recently conducted by the OECD and Harvard University on the education conditions faced in countries and on the approaches adopted to sustain educational opportunity during the pandemic has found that the learning that has taken place during the period when schools were closed was at best only a small proportion of what students would have learned in school (Schleicher and Reimers, 2020. The period of learning at home has made visible the many benefits that students gain from being able to learn in close contact with their teachers and peers, and with full access with the wide variety of educational, social and health-related services which schools offer.

This public awareness of the importance of schools and of teachers could be strategically deployed to increase engagement and support from parents and communities for schools and for teachers. This will be particularly important in the current context as the health and economic costs of the pandemic risk reducing the funds available to education. There are unquestionable benefits to reopening educational institutions in terms of supporting the development of knowledge and skills among students and increasing their economic contribution over the longer term, in fact, the learning loss which has already taken place, if left remedied, is likely to exact on economic toll on societies in the form of reduced productivity and growth. Reopening schools will also bring economic benefits to families by enabling them to return to work once public health authorities deem that this is feasible.

Teacher's preparedness to support digital learning

During the pademic, remote learning became a lifeline for education but the opportunities that digital technologies offer go well beyond a stopgap solution during a crisis. Digital technology offers entirely new answers to the question of what people learn, how they learn, and where and when they learn. Technology can enable teachers and students to access specialised materials well beyond textbooks, inmultiple formats and in ways that can bridge time and space. Working alongside teachers, intelligent digital learning systems don’t just teach students science, but can simultaneously observe how they study, the kind of tasks and thinking that interest them, and the kind of problems that they find boring or difficult. The systems can then adapt the learning experience to suit students’ personal learning styles with great granularity and precision. Similarly, virtual laboratories can give students the opportunity to design, conduct and learn from experiments, rather than just learning about them. Moreover, technology does not just change methods of teaching and learning, it can also elevate the role of teachers from imparting received knowledge towards working as co-creators of knowledge, as coaches, as mentors and as evaluator’s That being said, the COVID-19 crisis struck at a point when most of the education systems covered by the OECD’s 2018 round of the Program for international Student Assessment (PISA) were not ready for the world of digital learning opportunities. A quarter of school principals across the OECD said that shortages or inadequacy of digital technology was hindering learning quite a bit or a lot, a figure that ranged from 2% in Singapore to 30% in France and Italy (OECD, 2019|. ). Those figures may even understate the problem, as not all principals will be aware of the opportunities for instruction that modern technology can provide

Class size, a critical parameter for the reopening of schools

To ensure all students have the opportunity to benefit from face-to-face teaching in a context of reduced class sizes, schools in about 60% of OECD member and partner countries are organising shifts to alternate students throughout the day when they cannot accommodate them all on site (Schleicher and Reimers, 2020[,). Unless schools can establish effective forms of hybrid learning which combine on-site and online learning experiences, the consequence of such a measure will be reduced classroom instruction time than before school closures. Distance learning has therefore remained in place in most countries until the end of the academic year to continue to support students, including for those who have opted not to or cannot attend class for sanitary or personal health reasons. While returning to school is compulsory in most OECD countries for students in the permitted age groups or specific levels of education (except for sick students or those with a vulnerable or sick family member), attendance is optional in Canada, the Czech Republic, France, and Spain, with remote and online learning for students who wish to stay at home. These hybrid measures air to secure support for there opening of schools while optimising their capacity for social distancing (Schleicher and Reimers,2020

Vocational educational during the COVID-19 lockdown

While remote learning has offered some educational continuity when it comes to academic learning, vocational education and training (VET} has been particularly hard hit by the crisis. Compared to general program, VET programmers suffer a double disadvantage as social distancing requirements and the closure of enterprises have made practical and work- based learning that are so crucial for the success of vocational education difficult or impossible. Yet, this sector plays a central role in ensuring the alignment between education and work, the successful transition of students into the labor market, and for employment and the economic recovery more generally.

Not least, many of the professions that formed the backbone of economic and social life during the lockdown hinge on vocational qualifications